Many investors fell for emerging markets in recent years when they delivered sizeable returns. More recently, the associated risk has reasserted itself and the infatuation has faded. To paraphrase Kenny Rogers, “You got to know when to hold ’em, fold ‘em, walk away, and run.” So what is an investor to do?

A major theme in media commentary since the turn of the century has been the prospect of a gradual passing of the baton in global economic leadership from the world’s most industrialized nations to the emerging economies. Anticipating this change, investors have sought greater exposure to these changing economic forces by including in their portfolios an allocation to some of the emerging powerhouses such as China, India, and Brazil.

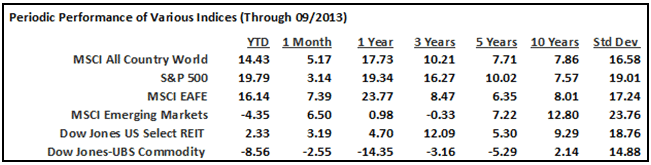

An emerging market is broadly defined as the market of an economy that is in the process of rapid growth and industrialization. The table shows that these markets historically have provided higher average returns than developed markets. But the flipside of these returns is that emerging markets also tend to be riskier and more volatile. That’s because their systems of law, ownership, and regulation are still developing, and they are often less politically stable. This is reflected in their higher standard deviation of returns, which is one measure of risk.

The risk associated with emerging markets has reasserted itself in recent months. Expectations of the US Federal Reserve “tapering” back its monetary stimulus have led to a retreat by many investors from these developing markets.

The risk associated with emerging markets has reasserted itself in recent months. Expectations of the US Federal Reserve “tapering” back its monetary stimulus have led to a retreat by many investors from these developing markets.

In its latest economic assessment released in September, the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) noted that while advanced economies were growing again, some emerging economies were slowing. They wrote, “One factor has been a rise in global bond yields—triggered in part by an expected scaling back of the US Federal Reserve’s quantitative easing—which has fueled market instability and capital outflows in a number of major emerging economies, such as India and Indonesia,” the OECD said.

Naturally, many investors will be feeling anxious about these developments and wondering whether emerging markets still have a place in their portfolios. There are number of points to make in response to these concerns. First, this information is in the price. Markets reflect concerns about the impact on capital flows of the Fed tapering. Changing a portfolio allocation based on past events is tantamount to closing the stable door after the horse has bolted.

Second, just as rich economies and markets like the US, Japan, Britain, and Australia tend to perform differently from one another, emerging economies and markets tend to perform differently from rich ones. This just means that irrespective of short-term performance, emerging markets offer the benefit of added diversification. And we know that historically, diversification across securities, sectors, industries and countries has been a good source of risk management for a portfolio.

Third, emerging markets perform differently from one another, and it is extremely difficult to predict with any consistency which countries will perform best and worst from year to year. That’s why concentrated bets are not advised. Rather than taking a bet on individual countries or even groups of countries (like the “BRICs”), the key to investing in emerging markets is to take a cautious approach—investing in a number of countries, keeping an eye on costs, and regularly reviewing risk controls.

Fourth, in judging your exposure to emerging markets, it is important to distinguish between a country’s economic footprint and the size of its share market. According to the IMF, the world’s 20 biggest economies last year, ranked in order by GDP in current prices and in US dollars, were the US, China, Japan, Germany, France, the UK, Brazil, Russia, Italy, India, Canada, Australia, Spain, Mexico, South Korea, Indonesia, Turkey, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, and Switzerland.

Of that top 20, eight nations are classed by index providers as emerging markets: China, Brazil, Russia, India, Mexico, South Korea, Indonesia, and Turkey. Yet despite the size of those individual economies, the size of their markets in a global sense is relatively small. China makes up only about 2% of the global market—and that is the biggest single emerging market. Combined, emerging markets currently make up 11% of the total world market.

This is not to downplay the importance of emerging markets. The global economy is changing, and the internationalization of emerging markets in recent decades has allowed investors to invest their capital more broadly. Emerging markets are part of that. The increasing opportunities for investment also increase diversification, so while one group of markets, countries, or sectors experiences tough times, another group may be posting strong returns.

While emerging market performances in recent times have been less than stellar, it is important to remember that they are still providing a diversification benefit and higher expected returns are likely to be realized over the long term. We know that risk and return are related, so getting out of emerging markets or reducing one’s exposure to them after stock prices have dropped means forgoing the increased expected return potential.

If anything, one should consider increasing their targeted allocation to emerging markets, precisely because they have had such a bumpy ride recently. After all, price and value are inversely related. While Kenny’s song doesn’t have lyrics to fit exactly this situation, you can at least eliminate the fold em’, walk away, and run options.

Kevin Kroskey, CFP®, MBA is President of True Wealth Design, an independent investment advisory and financial planning firm that assists individuals and businesses with their overall wealth management, including retirement planning, tax planning and investment management needs.