Uncertainty around what your health care costs will be in retirement is a troubling concern for even the healthiest of savers. I have reviewed recent studies with widely varied estimates of needing $65,000 and $200,000 per person at retirement for healthcare. These estimates also don’t factor in the cost of long-term care – a real risk and fear that many financial salespeople capitalize on to sell you commissioned products.

I’d propose another way to think about these potential expenses, based on actual evidence. I believe what results is smarter planning likely to produce better outcomes.

HOW HIGH WILL HEALTHCARE GO?

In terms of average yearly costs, a 2016 Fidelity estimate concluded, “The average 65+ retiree today should expect to pay around $5,000 a year on health care premiums and out-of-pocket expenses.” Other studies find similar results. Viewed as a yearly cost versus a lump sum needed at retirement, healthcare is more palatable.

Everyone knows healthcare increases over time. And while healthcare costs do consume more of total expenditures in the later years of retirement, going from 5% at age 60 to 15% by age 80 according to a 2013 Morningstar study, these increases are more than offset with decreased spending in other categories. In aggregate, total inflation-adjusted spending, including healthcare, declines as you age.

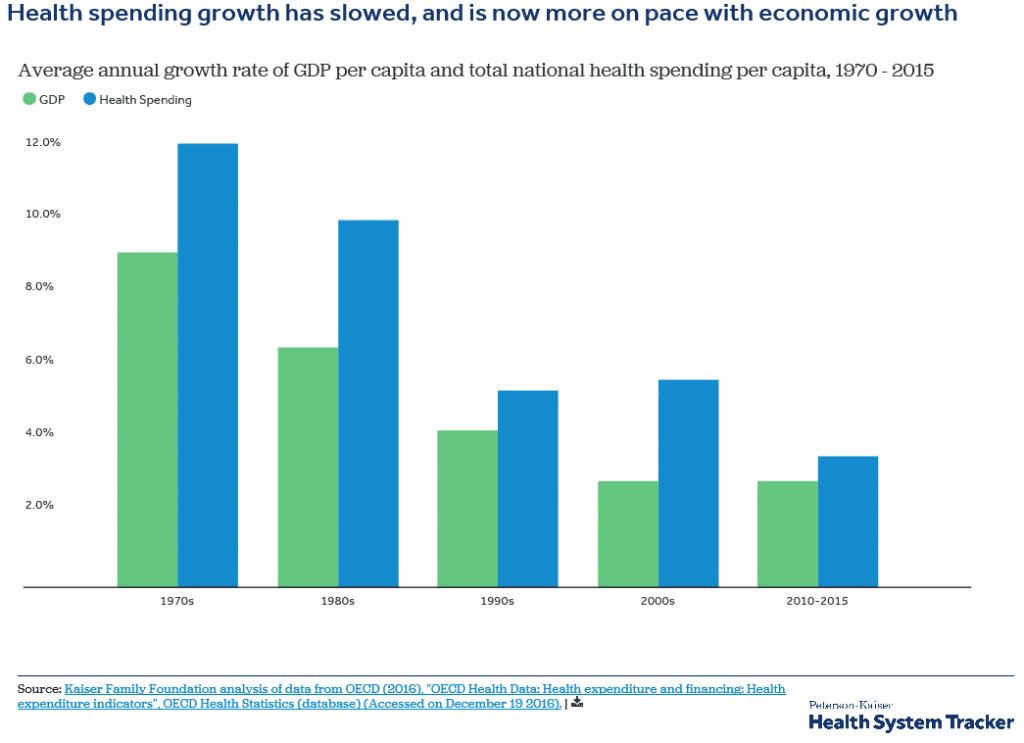

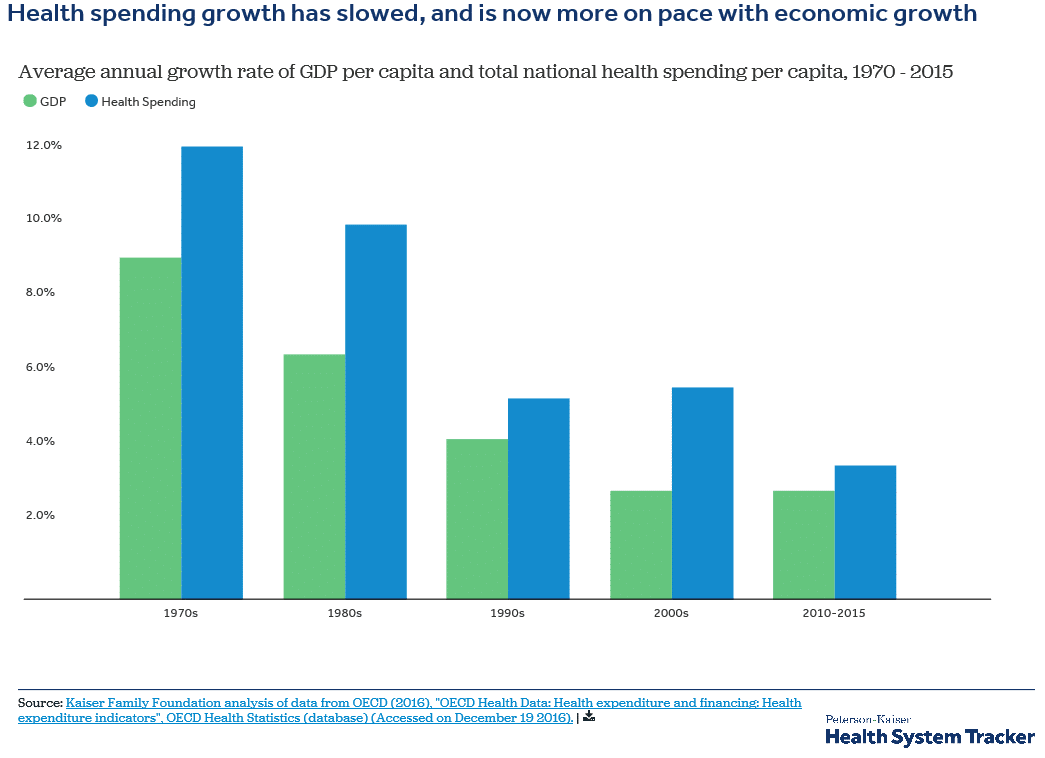

About those cost increases: healthcare today is 17 percent of America’s Gross Domestic Product, compared with only 5 percent back in 1960. It is projected to grow to 20% by 2025. However, the growth rate in healthcare spending relative to the general price increases (inflation) was much higher in the 1960s-1980s and less so in the 1990s. Starting in 2008, health spending growth slowed to a similar rate as inflation and remained relatively stable at about 3 percent growth per year. In 2014-2015, health spending began to grow more rapidly with the Affordable Care Act’s coverage expansion.

Math and economics dictate that healthcare cost growth at a rate higher than general inflation cannot continue indefinitely. Healthcare begins crowding out other spending and economic growth. The higher prices can no longer be afforded and the trend changes. Yet, no one knows when the trend will change. Thus, to be conservative, you should use a higher rate of inflation for your healthcare retirement expenses compared to other lifestyle expenses. Yet, if actual expenses come in less than projections over time, you can then afford to spend the money somewhere else.

BEFORE YOU BUY A POLICY, READ THIS

Statistics show that 69 percent of all 65-year olds today can expect to need some form of long-term care (LTC) and the average duration for using any services is about 3 years. These numbers are regularly quoted and do not reveal wide variations in actual dollars spent. After all, using LTC services at home for a couple months is relatively insignificant financially compared to a multi-year stay in a nursing home.

For successful retirees, the primary risk is a large dollar expense for a multitude of years – generally a nursing home. With the national average cost for a stay in a nursing home upwards of $7,000 per month, the fear is that long-term care costs will drain away lifetime savings, restrict access to care, and make you or your surviving spouse dependent on your family. Enter: long-term care insurance.

New evidence from the Center for Retirement Research finds this risk isn’t as bad as advertised. They find the probability of ever using nursing home care is 44% for men and 58% for women with the average years spent in care 0.88 and 1.44, respectively. Only 8% of men and 15% of women require nursing home care for three years or more.

Insurance can be a good tool when you have a risk that has a low-probability of an occurrence with a high-cost loss. For example, life insurance: even though there is a low probability of premature death in your 30s or 40s, you bought life insurance to transfer the risk of a high-cost loss and protect your family. The evidence on long-term care show us that we have the reverse situation: a high-probability of occurrence with a low-cost risk in most cases.

While LTC risks need to be considered in the context of a retirement plan, I regularly find that with proper planning it is not necessary or does not make financial sense to buy LTC insurance to transfer this risk.

________________________________________________

Kevin Kroskey, CFP®, MBA is President of True Wealth Design, an independent registered investment advisory and wealth management firm specializing in retirement, tax, and investment planning.